Myasthenia gravis (MG) isn’t just muscle weakness. It’s your body turning against itself - attacking the connection between nerves and muscles until even simple tasks like smiling, swallowing, or holding up your head feel impossible. It’s not rare. Around 1 in 5,000 people in the UK and US live with it. And for decades, treatment meant balancing side effects from steroids and immunosuppressants just to stay functional. But today? The game has changed. Since 2020, and especially in 2024 and 2025, we’ve seen a wave of targeted therapies that don’t just manage symptoms - they reset the immune system’s attack on the neuromuscular junction. This isn’t theory. It’s real, measurable change for people who were once stuck on high-dose prednisone with broken bones and diabetes.

How Myasthenia Gravis Actually Works

At the core of MG is a broken signal. Your nerves send messages to your muscles using a chemical called acetylcholine. But in MG, your immune system makes antibodies that block or destroy the receptors where acetylcholine docks. Without that connection, muscles don’t get the signal to contract. That’s why symptoms get worse with use - your muscles tire out because the signal keeps failing.

About 85% of people with generalized MG have antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR). Another 5-8% have antibodies against MuSK, a different protein involved in nerve-muscle communication. And then there’s the 5-10% who test negative - no known antibody, but still the same symptoms. That’s why treatment can’t be one-size-fits-all. The type of antibody you have affects which drugs work best.

Thymus gland involvement is another key piece. In about 10-15% of cases, there’s a thymoma - a tumor on the thymus. But even without a tumor, the thymus is often abnormal in MG patients. That’s why removing it (thymectomy) became standard care after the 2016 MGTX trial showed it cut steroid use by 56% and hospitalizations by 67% over three years.

First-Line Treatments: Symptomatic Relief and Immunosuppression

Most people start with pyridostigmine (Mestinon). It doesn’t fix the immune problem. It just slows down the breakdown of acetylcholine, giving more of it a chance to bind to the remaining receptors. Doses range from 60 to 120mg every 3 to 6 hours. Side effects? Nausea, cramps, diarrhea - affecting up to 45% of users. But for many, it’s the only thing that lets them get through the day without a wheelchair.

Then comes prednisone. It’s fast. 70-80% of patients see improvement within weeks. But the cost? High. Weight gain hits 65% of users. Osteoporosis develops in 1 in 4 after just one year. Diabetes shows up in 15-20%. That’s why doctors don’t keep people on high doses forever. The goal is to taper down as soon as another drug kicks in.

That’s where long-term immunosuppressants come in:

- Azathioprine: Taken daily, takes 6-18 months to work. 60-70% respond. Side effects: low white blood cells (10%), liver damage (5%).

- Mycophenolate: 1,000-1,500mg twice a day. 65-75% response rate. Gastro issues in 30% - nausea, vomiting, diarrhea.

- Cyclosporine: 90% effective, but 30% get high blood pressure, 25% develop kidney damage. Often avoided unless other options fail.

These drugs are cheap - $500 to $2,000 a year - but slow. And the side effects are brutal. That’s why many patients wait until they’ve tried two of these before moving to newer therapies.

Targeted Biologics: The New Standard

The biggest shift since 2020 has been the rise of biologics - drugs that target specific parts of the immune system. They’re expensive, but they’re precise. And for many, they’re life-changing.

Complement inhibitors - like eculizumab and ravulizumab - stop the immune system from destroying the neuromuscular junction at the final step. They’re only for AChR-positive MG. Eculizumab is given IV every two weeks after an initial four-week loading. It works in about 88% of patients, with over half reaching minimal manifestation status - meaning near-normal function. But there’s a catch: you must get meningococcal vaccines before starting. The risk of deadly meningitis without them is real. Annual cost? $500,000-$600,000.

FcRn inhibitors - like efgartigimod, rozanolixizumab, and nipocalimab - are different. They don’t block complement. They remove IgG antibodies from the bloodstream. That means they work for AChR, MuSK, and even seronegative MG. Efgartigimod is given IV weekly for four weeks, then repeated every 4-8 weeks. Rozanolixizumab is a weekly shot under the skin. Nipocalimab, approved in April 2025, works monthly. All reduce IgG by 60-80%. Onset? Just 1-2 weeks. In the ADAPT SERON study, 68% of seronegative patients improved with efgartigimod - a breakthrough.

For MuSK-positive MG, rituximab is often the go-to. It wipes out B-cells that make the bad antibodies. Two doses, two weeks apart. Response? Up to 80% in MuSK-MG, but only 50-60% in AChR-MG. It takes 8-16 weeks to work, but the effect can last a year or more. Cost? $10,000-$15,000 per course.

Thymectomy: Surgery That Can Change the Course

If you’re AChR-positive, between 18 and 65, and otherwise healthy, thymectomy is recommended within the first year of diagnosis. The MGTX trial showed 35-40% of patients achieved stable remission five years after surgery - compared to just 15-20% on medication alone.

Today, most thymectomies are done minimally invasively - either with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or robotic tools. Recovery is faster. But long-term outcomes for these newer methods are still being studied. Still, 82% of patients in MGFA surveys say they’re satisfied with the results. That said, 35% still deal with fatigue a year later. Surgery isn’t a cure-all. But it’s often the key to reducing or eliminating lifelong drugs.

Choosing the Right Path

There’s no single best treatment. It depends on your antibody status, age, severity, and lifestyle.

For mild cases? Start with pyridostigmine and a low dose of prednisone. Add azathioprine or mycophenolate if symptoms don’t improve in 3-6 months.

For moderate to severe AChR-positive MG? Many neurologists now start with an FcRn inhibitor like rozanolixizumab - especially if you want to avoid IV infusions. If you’re in a hospital with high infection risk or need fast control, eculizumab may be better.

For MuSK-MG? Rituximab is often first-line after pyridostigmine. It’s cheaper than biologics and highly effective.

For seronegative MG? FcRn inhibitors are now the only proven targeted option. Efgartigimod and rozanolixizumab both work here - something we didn’t know five years ago.

And if you’re young, healthy, and AChR-positive? Thymectomy should be on the table - even if you’re doing well on meds. It might be the only way to get off steroids long-term.

Real People, Real Outcomes

On patient forums, stories are changing. One woman in Birmingham, 52, switched from prednisone to rozanolixizumab after three years of bone fractures and weight gain. She started getting injections every week. Within three weeks, she could walk to the shop without stopping. “I haven’t felt this normal since I was 30,” she said.

But it’s not all smooth. A man in Leeds spent six months fighting insurance for eculizumab. His claim was denied three times. He had to get a neurologist’s letter, a letter from his GP, and a letter from his pharmacist. He finally got approved - but only after missing two weeks of work and nearly losing his job.

Cost is the biggest barrier. In the US, 40% of eligible patients can’t get insurance approval. In the UK, NHS access varies by region. Some trusts approve FcRn inhibitors quickly. Others still make patients try five immunosuppressants first - even though guidelines say that’s outdated.

What’s Coming Next

The future is moving fast. In 2025, phase 1 trials began for CAR T-cell therapy targeting B-cell maturation antigen. Early results show 60% remission in refractory MG - a potential cure.

Biomarkers are improving too. New IgG4-specific tests, expected in 2026, may let doctors track disease activity without waiting months for symptoms to change.

And then there’s agrin mimetics - experimental drugs that help rebuild the damaged nerve-muscle connection. Animal studies show 40% less damage. Human trials could start by 2027.

For now, the goal is minimal manifestation status - where symptoms are barely noticeable. That’s achievable now. Not in 10 years. Now.

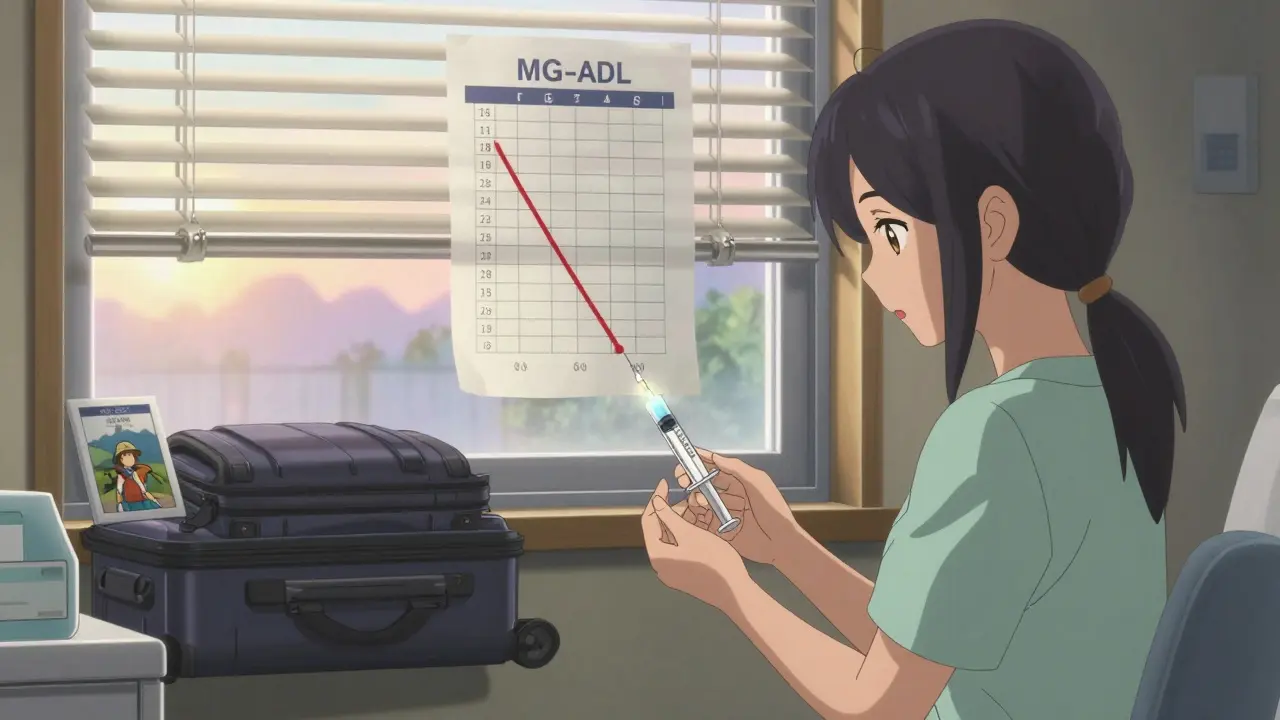

Support and Monitoring

Tracking your progress matters. Doctors use two tools: the MG-ADL (Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living) score and the QMG (Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis) score. These are simple checklists - how many times did you struggle to climb stairs? Can you hold your head up? - scored from 0 to 39. A drop of 3-5 points means real improvement.

Check-ins should happen every 4-12 weeks. Antibody levels? Don’t rely on them. They change slowly. Symptoms change faster. That’s why the scores matter more.

Support is critical. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America runs a 24/7 nurse hotline. In the UK, the MG Association offers local support groups. Over 15,000 people use them every year. You’re not alone. And help is just a call away.

Comments

This is why America needs to stop letting Big Pharma control everything!!! $600K for a drug?!?! I can buy a LAMBORGHINI for that!! 😤💸🇺🇸 We’re being ROBBED! My cousin’s sister had MG and they made her wait 14 months for insurance approval-she ended up in a wheelchair! FIX THE SYSTEM!! #MedicareForAll #StopPharmaGreed

Okay, I’m crying. I’ve been following MG research since my mom was diagnosed in 2019. The fact that FcRn inhibitors work for SERONEGATIVE patients???! Like… holy. 🥹 I remember her saying, 'I’m just a ghost in my own body.' Now she’s gardening again. Rozanolixizumab gave her back her life. This isn’t just science-it’s miracles in vials. 🌸💉

FcRn inhibition ≠ cure. IgG depletion is a band-aid. You’re not modulating the autoimmune cascade-you’re just flushing antibodies. The thymus remains dysregulated. And without Treg restoration, relapse is inevitable. This is palliative immunology. Don’t mistake efficacy for resolution.

this is so hopefull!! i have a friend in delhi with mg and she cant even get mestinon here 😔 but the part about rozanolixizumab working for seronegative?? wow!! i will share this with her family!! thank you for writing this!! 🙏❤️

I’m so tired of people acting like biologics are the only answer. My sister got thymectomy in 2021 and went into remission. No drugs. No infusions. Just surgery and patience. Why are we pushing expensive, risky treatments when the cure is already in the chest? 🤷♀️ #ThymectomyWorks

There’s something deeply human about this. We’ve spent centuries treating symptoms. Now we’re finally targeting the war inside the body-not just the battlefield. But the cost? The bureaucracy? The waiting? That’s the real disease. Medicine advanced. Society didn’t. We cured the body but left the soul in triage.

To anyone reading this who feels alone: you’re not. I’m a nurse in Ohio, and I’ve seen patients go from barely breathing to hiking with their grandkids on FcRn inhibitors. It’s not magic. It’s science. And it’s here. Keep fighting for your care. Your voice matters. 💪❤️

Let’s be honest-most of these 'breakthroughs' are just repackaged immunosuppressants with a fancy name and a six-figure price tag. The thymectomy data from MGTX is 8 years old. Why are we still hyping this as revolutionary? The real innovation is in the marketing department. 🤨

You guys are missing the point. If you’re AChR+ and under 65, thymectomy should be mandatory. Not 'considered.' Mandatory. This whole biologics thing is just Big Pharma’s way of keeping you hooked on lifetime infusions. Surgery is cheaper, permanent, and doesn’t require a second mortgage.

I just want to say thank you to the person who wrote this. I read it out loud to my mom last night. She’s 68, seronegative, and has been on azathioprine since 2017. She cried. Not because she’s sad-because for the first time, she felt seen. We’re gonna ask her neurologist about rozanolixizumab next week. You gave us hope. 🤍

I am writing to express my profound appreciation for this exceptionally well-researched and thoughtfully articulated exposition on the current therapeutic landscape of myasthenia gravis. The inclusion of both clinical data and patient narratives is not merely informative-it is profoundly humanizing. I shall be sharing this with my colleagues at the Montreal Neurological Institute. 🙏