What Exactly Is a Pulmonary Embolism?

A pulmonary embolism (PE) happens when a blood clot blocks one or more arteries in your lungs. These clots usually start in the deep veins of your legs - a condition called deep vein thrombosis (DVT). About 70% of all PEs come from clots that travel from the legs up to the lungs. Once the clot gets stuck in the pulmonary artery, it cuts off blood flow to part of the lung. That means less oxygen gets into your bloodstream, and your heart has to work harder to pump blood through the blocked area.

This isn’t just a minor issue. A large clot can cause sudden collapse, organ damage, or even death. The American Lung Association estimates that around 100,000 people in the U.S. die from PE every year. Many of those deaths could be prevented - if the condition is caught early.

Why Sudden Shortness of Breath Is the Biggest Red Flag

If you’ve ever felt like you couldn’t catch your breath after climbing a flight of stairs, you know how uncomfortable that feels. But with a pulmonary embolism, the shortness of breath comes out of nowhere - even when you’re sitting still. According to clinical data from the National Institutes of Health, sudden shortness of breath is the most common symptom, appearing in 85% of confirmed PE cases.

It doesn’t always feel the same. If the clot is large and blocks a major artery, the breathlessness is severe and immediate. You might feel like you’re suffocating, even while lying down. Smaller clots might cause milder symptoms that come and go, which is why people often ignore them. One patient on the American Lung Association’s forum described breathing difficulties for three weeks before being diagnosed - her doctor thought it was anxiety.

Don’t wait for it to get worse. If you suddenly can’t breathe normally - especially if you’ve been sitting for long periods, recently had surgery, or have a history of blood clots - get checked right away.

Other Symptoms You Might Miss

Shortness of breath is the main sign, but PE doesn’t come with a checklist. Other symptoms can be confusing because they mimic heart attacks, asthma, or even the flu.

- Chest pain: About 74% of patients feel sharp, stabbing pain that gets worse when they breathe in or cough. It’s often mistaken for a heart problem.

- Cough: Happens in over half of cases. If you’re coughing up blood (hemoptysis), that’s a major warning sign - it occurs in 23% of PE patients.

- Leg swelling or pain: If one leg is suddenly swollen, warm, or tender, especially in the calf, you might have a clot that hasn’t moved yet. This happens in 44% of cases.

- Fainting or dizziness: Around 14% of people with PE pass out. This usually means the clot is large enough to strain the heart.

- Rapid heartbeat: A heart rate over 100 beats per minute is common. It’s your body’s way of trying to compensate for low oxygen.

- Fast breathing: Breathing more than 20 times a minute is a sign your body is struggling to get enough oxygen.

Many people go to the doctor with just one or two of these symptoms. That’s why PE is so often missed. A 2022 survey found 68% of PE patients visited a healthcare provider at least twice before getting the right diagnosis. One person was told they had pneumonia. Another was given asthma inhalers.

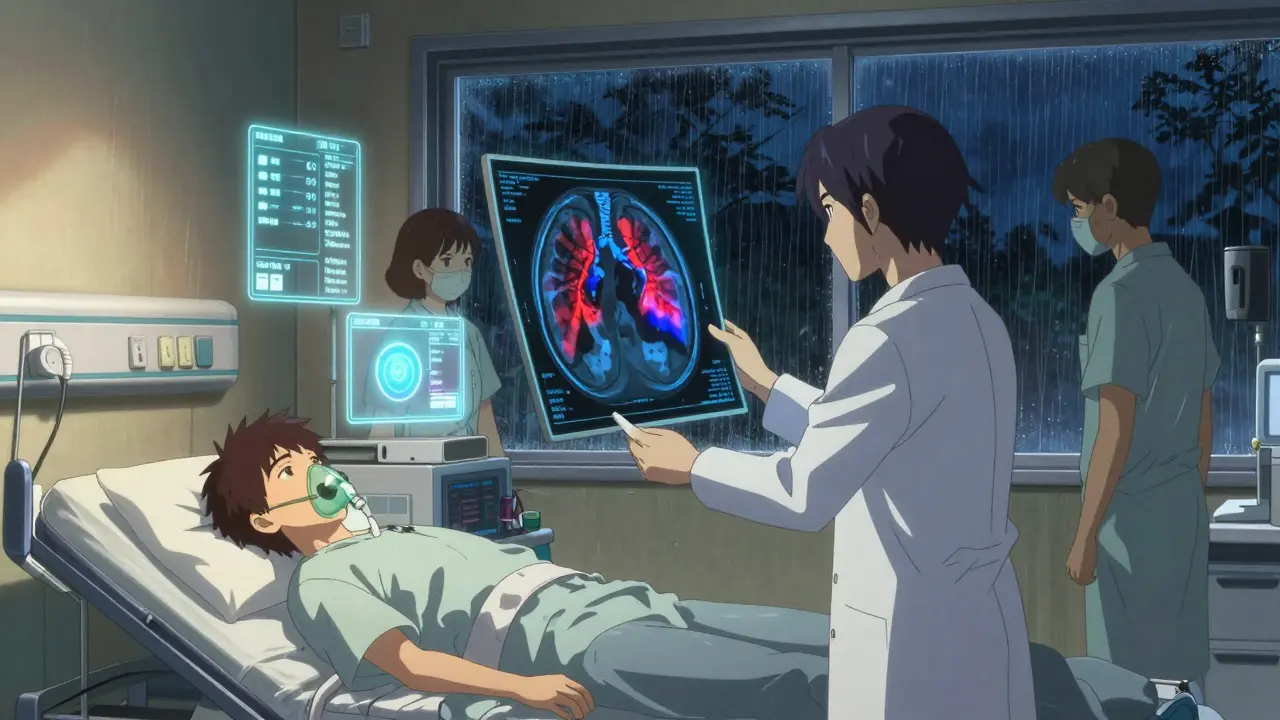

How Doctors Diagnose Pulmonary Embolism

There’s no single test that confirms PE right away. Doctors use a step-by-step approach based on your symptoms, risk factors, and test results.

First, they assess your risk using tools like the Wells Criteria or the Geneva Score. These aren’t magic formulas - they’re questionnaires that ask things like: Have you had recent surgery? Are you immobilized? Do you have leg swelling? Is your heart rate high? Based on your answers, you’re labeled as low, moderate, or high risk.

If you’re low risk and your D-dimer test is negative, PE is almost certainly ruled out. The D-dimer test checks for a protein fragment that appears when clots break down. A result below 500 ng/mL means there’s less than a 3% chance you have a clot - and you can go home without further testing.

But here’s the catch: D-dimer isn’t perfect. In people over 50, false positives go up. That’s why doctors now use age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds. For someone who’s 70, a result under 700 ng/mL might still be normal. This change has cut down unnecessary scans by over a third.

The Gold Standard: CTPA Scan

If your risk is moderate or high, or if your D-dimer is elevated, the next step is usually a CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA). This is a special CT scan that uses contrast dye to show blood flow in your lungs. It’s the most accurate test available - detecting PE in 95% of cases.

The scan takes less than 10 minutes. You’ll get a shot of iodine-based contrast through an IV, then lie still while the machine takes detailed images of your pulmonary arteries. Radiation exposure is low - about the same as a cross-country flight. But it’s not for everyone. If you’re allergic to contrast or have kidney problems, doctors use a different test: a ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan.

V/Q scans don’t use contrast. Instead, you inhale a harmless gas and get a radioactive tracer injected. The scan shows which parts of your lungs are getting air and which aren’t getting blood. It’s less common now, but still vital in places without advanced CT equipment or for patients who can’t have contrast.

What If You’re in Immediate Danger?

Some people with PE are unstable - their blood pressure drops, they faint, or their heart starts racing uncontrollably. In these cases, doctors don’t wait for scans. They go straight to an echocardiogram, which is an ultrasound of the heart.

If the right side of the heart is enlarged or struggling to pump, it’s a strong sign of a massive PE. This is a medical emergency. Treatment starts immediately with clot-busting drugs or even surgery to remove the clot. Delaying even 30 minutes can be deadly.

Why Some People Keep Getting PE

Having one PE doesn’t mean you’re out of the woods. About one in three people who’ve had a PE will get another within 10 years. That’s why doctors look for underlying causes.

Cancer patients have nearly five times the risk of PE. Blood thinners are often needed long-term for them. People with inherited clotting disorders, those on hormone therapy, or those who’ve had recent surgery or trauma are also at higher risk.

And if you’ve had a clot before, your body remembers. Doctors don’t treat every episode the same. Past history changes how aggressively they test and treat the next one.

What’s Changing in PE Diagnosis Today

Diagnosis is getting faster and smarter. Hospitals now use Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams (PERT) - groups of specialists who jump in when PE is suspected. These teams cut the time from symptom onset to treatment by over three days and reduce death rates by 4%.

Artificial intelligence is helping too. New algorithms can analyze CTPA scans in seconds, spotting clots that even experienced radiologists might miss. One AI tool called PE-Flow correctly identified clots in 96% of cases in a recent trial.

There’s also new research into blood biomarkers beyond D-dimer. Scientists are testing combinations of proteins that signal clot formation earlier and more accurately. Early results from the DETECT-PE trial show a 98.7% accuracy rate in ruling out PE in intermediate-risk patients.

What You Can Do

You can’t always prevent a pulmonary embolism, but you can reduce your risk:

- Move regularly - especially after surgery or long flights.

- Stay hydrated and avoid sitting for hours without stretching.

- Know your family history. If someone in your family had unexplained clots, tell your doctor.

- If you’re on birth control or hormone therapy, discuss your clotting risk with your provider.

- Don’t ignore sudden breathlessness, chest pain, or leg swelling - even if you think it’s "just anxiety."

Most importantly: if you feel like you’re struggling to breathe and it’s new, unexplained, and sudden - don’t wait. Go to the emergency room. PE doesn’t always warn you. But it can be stopped - if you act fast.

Can a pulmonary embolism go away on its own?

Small clots can sometimes dissolve naturally over weeks or months, especially if you’re on blood thinners. But you can’t rely on this. A clot that’s large or in a critical artery won’t dissolve safely without treatment. Waiting increases the risk of lung damage, heart strain, or sudden death. Even if symptoms seem to improve, medical evaluation is always needed.

Is a pulmonary embolism the same as a heart attack?

No. A heart attack happens when a clot blocks blood flow to the heart muscle. A pulmonary embolism blocks blood flow to the lungs. But they can feel similar - both cause sudden chest pain, shortness of breath, and rapid heartbeat. That’s why doctors check for both. An EKG and blood tests help tell them apart. Misdiagnosing PE as a heart attack can delay life-saving treatment.

How long does it take to recover from a pulmonary embolism?

Recovery varies. Most people start feeling better within a few weeks after starting blood thinners. But full recovery - meaning your lungs and heart return to normal function - can take months. Some people develop long-term lung damage called chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), which requires ongoing treatment. Follow-up scans and doctor visits are essential to monitor progress.

Can you get a pulmonary embolism without having DVT?

It’s rare, but possible. While most clots start in the legs, they can also form in the arms (especially after IV lines), pelvic veins, or even the heart. In very rare cases, clots form spontaneously due to genetic disorders or cancer. If no DVT is found, doctors will look for other sources - including tumors or inherited clotting conditions.

Are there alternatives to CT scans for diagnosing PE?

Yes. If you can’t have contrast dye (due to allergy or kidney issues), a V/Q scan is the main alternative. It’s less detailed than a CT scan but still very accurate for ruling out PE. In emergencies, doctors may use ultrasound to check for leg clots - if a large clot is found in the thigh, they’ll treat for PE even without a lung scan. Newer tools like AI-assisted ultrasound and blood biomarkers are also emerging, but CTPA remains the standard where available.

Comments

I had a PE last year after a long flight 🥲 honestly thought it was just anxiety until I passed out in the grocery store. Don't ignore sudden breathlessness. I'm alive because I went to the ER. You're not being dramatic if you can't breathe.

Okay but why do doctors still act like PE is some mysterious villain when it's basically just a blood clot that got lazy and took a nap in your lungs? I had three friends with this and all of them were told it was asthma or panic attacks for WEEKS. Like maybe stop assuming everyone's just stressed and actually check for clots? The D-dimer thing is fine but why does it take three visits and a near-death experience to get a CTPA? I'm exhausted.

This is one of the clearest explanations I've ever read on PE. I'm a nurse in rural Ohio and we don't always have immediate access to CTPA scans. The V/Q scan info was especially helpful - I'll be sharing this with my team. Thanks for breaking down the risk factors and the age-adjusted D-dimer. So many people don't realize how much the guidelines have changed.

So let me get this straight - you're telling me that if I sit on my butt for 12 hours during a flight and then can't catch my breath, it's not just "being out of shape"? Shocking. And the part about doctors dismissing it as anxiety? Oh honey, that's the plot of every medical drama ever. But seriously - if you're breathing like you just ran a marathon while sitting in a recliner, call an ambulance. No one wants to be the person who "thought it was stress" and ended up on a ventilator.

If you're reading this and you're worried about your legs swelling or sudden breathlessness - please, just go. I know it's scary. I know you think it's nothing. I know you don't want to bother anyone. But I've sat in the ER waiting room watching people get rushed in with PE. One of them was 28 and had never smoked. It doesn't care how healthy you think you are. You're not wasting anyone's time. You're saving your life.

D-dimer is useless for women on birth control and over 40

I'm a software engineer who sits all day. This post made me stand up and walk around for the first time in 3 hours. Honestly? I didn't know PE could come from sitting. I thought it was just for people on long flights or after surgery. Now I'm stretching every hour. Small change. Big deal.

I had a PE in 2020 after a knee surgery and honestly the hardest part wasn't the clot it was the guilt I felt because I thought I caused it by not moving enough. But then I found out my mom had the same thing at 52 and no one knew why. Turns out genetics are a thing. So if you have family history even if you're active - tell your doctor. Don't wait for symptoms. And if you're on birth control? Ask about your clotting risk. It's not paranoia it's prevention

We treat PE like it's some kind of cosmic punishment for sitting too long but really it's just biology being indifferent. The body makes clots because it's trying to heal. But sometimes it gets confused. The real tragedy isn't the clot it's the system that waits until you're gasping before it listens. We need to stop glorifying "toughing it out" and start trusting the body's warning signs. PE doesn't care if you're productive or busy. It just wants to kill you quietly

Doctors are still clueless. I went 5 times before they did a scan. My sister died because they thought she had bronchitis. You people are lucky you're alive. Stop being polite and demand a CTPA if you have risk factors. No excuses. No waiting. No more "maybe it's anxiety". That phrase kills people