When your lung suddenly stops working like it should, it’s not just uncomfortable-it’s life-threatening. A pneumothorax, or collapsed lung, happens when air leaks out of the lung and gets trapped between the lung and chest wall. That air builds up pressure, pushing the lung down so it can’t expand properly when you breathe. It doesn’t always come with warning signs. Sometimes, it hits out of nowhere-even in healthy people. And if you don’t act fast, it can turn into a tension pneumothorax, where the pressure keeps rising, squashing your heart and other organs. This isn’t something you wait to see if it gets better. Time matters.

What Does a Collapsed Lung Actually Feel Like?

The pain is the first red flag. It’s not a dull ache or a muscle strain. It’s sharp, sudden, and stuck to one side of your chest-like someone stabbed you with an ice pick right under your ribcage. You’ll feel it most when you take a deep breath or cough. It’s so intense that many people stop breathing deeply without even realizing it. Some report the pain shooting up into the same-side shoulder, which is a classic clue doctors look for. In fact, 92% of confirmed cases show this shoulder radiation pattern. Breathlessness follows quickly. You might think you’re just out of shape, but if you’re sitting still and suddenly can’t catch your breath, that’s not normal. About 9 out of 10 people with pneumothorax report this. The worse the collapse, the worse the breathing trouble. If more than 30% of your lung has collapsed, you’ll feel short of breath even when you’re not moving. If it’s under 15%, you might only notice it when climbing stairs. But once you’re gasping at rest, you’re in danger territory. Other signs are harder to notice without a doctor’s training. Your breathing sounds quieter on the affected side-so quiet, a stethoscope picks up nothing. Your chest might sound hollow when tapped, like drumming on an empty barrel. And if you’re really sick, your skin might turn bluish, your heart races past 130 beats per minute, and your blood pressure drops. That’s tension pneumothorax. It’s rare, but deadly. And it doesn’t wait for X-rays.When Every Second Counts: Emergency Response

If you or someone else has sudden chest pain and trouble breathing, call emergency services immediately. Don’t drive yourself. Don’t wait for a doctor’s appointment. Don’t hope it’s just a pulled muscle. In the emergency room, the clock starts ticking the moment symptoms appear. For tension pneumothorax-where the pressure is crushing your heart-doctors don’t wait for imaging. If you’re pale, sweating, struggling to breathe, and your blood pressure is falling, they’ll stick a needle into your chest right away. This isn’t risky-it’s the only thing that can save your life in those minutes. Studies show that every 30-minute delay increases complication risk by over 7%. That’s why trauma teams are trained to treat it clinically, not by scan. For less severe cases, they’ll check your oxygen level. If it’s below 92%, you need a chest tube within 30 minutes. If it’s above 92% and you’re stable, they might just watch you for a few hours with repeat X-rays. But if your symptoms get worse? Immediate intervention kicks in. No waiting.How Do Doctors Know It’s a Collapsed Lung?

Chest X-ray is still the go-to test. It catches 85 to 94% of cases. But it’s not perfect. If you’re lying down after a car crash, up to 60% of pneumothoraces can be missed on X-ray. That’s why many ERs now use ultrasound-specifically, the E-FAST scan. In skilled hands, it’s 94% accurate and faster than waiting for an X-ray. The key sign? The “lung point.” That’s where the collapsed lung still touches the chest wall. Seeing it move in and out with breathing confirms the diagnosis. CT scans are the gold standard. They can spot as little as 50 milliliters of air-tiny leaks an X-ray would never catch. But they’re not used first. Too much radiation, too slow. They’re saved for complex cases or when the diagnosis is unclear. Blood tests help too. If your oxygen level is low and your carbon dioxide is too, it’s another clue. But they don’t diagnose-it’s the combination of symptoms, exam, and imaging that tells the story.

Treatment: From Watching to Surgery

Not every collapsed lung needs a tube or surgery. If it’s small-less than 2 cm of air on the X-ray-and you’re young and healthy, doctors might just give you oxygen and send you home to wait. Breathing pure oxygen helps your body absorb the trapped air faster. In 82% of these cases, the lung re-expands on its own within two weeks. If the collapse is bigger, they’ll try needle aspiration. A thin tube is inserted into the chest to suck out the air. It works in about 65% of cases. If that fails, or if you’re not improving, they’ll insert a chest tube. That’s a bigger tube, usually 28 French size, connected to a drainage system. It works in 92% of cases, but it’s not risk-free. Infection, bleeding, and fluid buildup in the lung after re-expansion can happen. For people who’ve had this more than once, or if they have underlying lung disease, surgery is often the best long-term fix. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) means tiny cuts, a camera, and tools to seal the leak. It cuts the chance of recurrence from 40% down to just 3-5%. Recovery takes a few days in the hospital, and it costs around $18,500 in the U.S.-but it’s worth it if you don’t want to go through this again.Who’s at Risk-and How to Avoid It

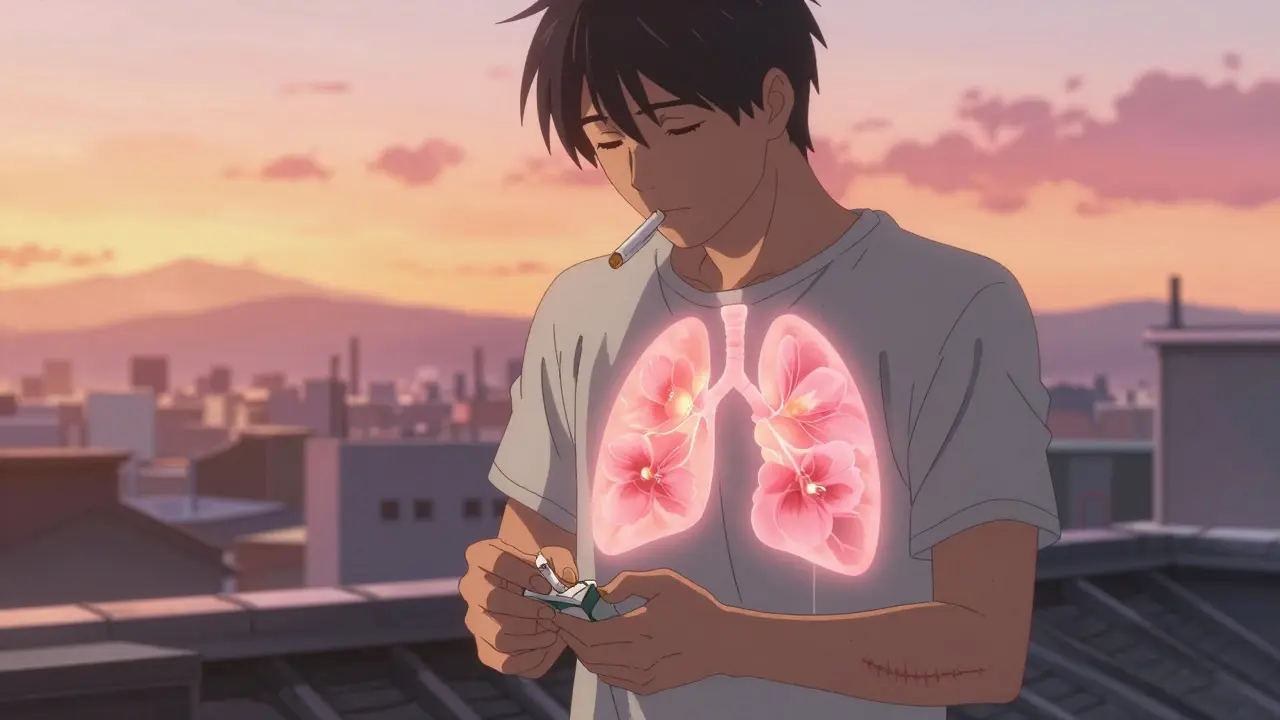

Men are six times more likely than women to get a spontaneous pneumothorax. Tall, thin people are at higher risk too-especially if they’re over 70 inches tall. But the biggest risk factor by far is smoking. If you’ve smoked more than 10 pack-years, your risk jumps 22 times higher. Quitting cuts your chance of it coming back by 77% in the first year. People with COPD, emphysema, cystic fibrosis, or tuberculosis are at much higher risk for secondary pneumothorax. And for them, the stakes are higher. While only 0.16% of healthy young people die from a first episode, 16% of older patients with lung disease die within a year. That’s why any collapse in someone with existing lung disease is treated as a medical emergency.

What Happens After You Leave the Hospital?

You can’t just go back to normal right away. Flying in a plane? Not for at least 2 to 3 weeks. The change in cabin pressure can make trapped air expand and cause another collapse. Scuba diving? Never, unless you’ve had surgery to prevent it. Even then, you need clearance. You’ll need a follow-up X-ray 4 to 6 weeks after the episode to make sure your lung fully re-expanded. About 8% of people have delayed problems if they skip this check-up. And if you’ve had two episodes on the same side? Doctors will strongly recommend surgery. The chance of a third collapse after two is 62%. That’s not luck-it’s a pattern.When to Go Back to the ER

Even after you’ve been discharged, you need to know the warning signs. If your chest pain suddenly gets worse, especially if it’s sharp and one-sided, call 999. If you start turning blue around your lips or fingers, or if you can’t speak in full sentences because you’re so short of breath, don’t wait. These are signs your lung has collapsed again-or worse, tension pneumothorax has returned. Most people who’ve had a pneumothorax recover fully. But it’s not something you can ignore. It doesn’t go away on its own if it’s big. And it doesn’t get better with rest if it’s getting worse. The difference between recovery and tragedy is knowing the signs-and acting before it’s too late.Can a collapsed lung heal on its own?

Yes, but only if it’s small and you’re otherwise healthy. For primary spontaneous pneumothorax with less than 2 cm of air on the X-ray, about 82% of cases resolve on their own within two weeks with supplemental oxygen. But if the collapse is larger, you have underlying lung disease, or you’re having trouble breathing, it won’t heal without medical intervention. Waiting too long can lead to tension pneumothorax, which is life-threatening.

Is pneumothorax the same as a pulmonary embolism?

No. A pneumothorax is air trapped outside the lung, causing it to collapse. A pulmonary embolism is a blood clot blocking an artery in the lung. Both cause sudden chest pain and shortness of breath, but they’re treated completely differently. A pulmonary embolism needs blood thinners; pneumothorax needs air removed from the chest cavity. Misdiagnosing one for the other can be deadly.

Can stress or anxiety cause a collapsed lung?

No. Stress and anxiety don’t cause pneumothorax. But they can make you hyperventilate, which might mimic the symptoms-sharp chest pain, feeling like you can’t breathe. If you’ve never had a collapsed lung before, anxiety is more likely. But if you’re tall, a smoker, or have lung disease, and you suddenly get sharp chest pain with breathing trouble, don’t assume it’s anxiety. Get checked.

How long does it take to recover from a chest tube?

Most people stay in the hospital 3 to 5 days after a chest tube is inserted. The tube stays in until no more air is leaking and the lung is fully expanded. Pain usually improves within a few days, but you’ll feel tired for a couple of weeks. Avoid heavy lifting and strenuous activity for at least 4 to 6 weeks. Full recovery depends on your age, overall health, and whether there was an underlying lung condition.

Does smoking increase the chance of a second collapsed lung?

Yes-dramatically. Smokers have a 22 times higher risk of a first pneumothorax. And if you keep smoking after one episode, your chance of a second one is over 60% within two years. Quitting cuts that risk by 77% in the first year. If you’ve had a collapsed lung, quitting smoking isn’t just a good idea-it’s the most important step you can take to avoid another one.

Can you fly after a pneumothorax?

No, not for at least 2 to 3 weeks after your lung has fully re-expanded and you’ve had a follow-up X-ray confirming it. The lower air pressure in airplane cabins can cause any remaining air to expand, triggering another collapse. The FAA and major medical societies require a clear chest X-ray and waiting period before air travel. If you’ve had surgery to prevent recurrence, you may be cleared after consulting with your surgeon.

Comments

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax in tall, thin males under 30 is classically idiopathic, but the real driver is subpleural bleb rupture. The lung’s visceral pleura lacks structural support in apical regions, making it vulnerable to alveolar rupture under minor pressure changes. Oxygen therapy accelerates nitrogen washout-Henry’s Law in action-allowing passive reabsorption at 12.5% of the air volume per day. Chest tube placement is indicated when collapse exceeds 2 cm or symptoms persist. VATS with bullectomy reduces recurrence to under 5% by excising the source, not just the symptom.

My brother had this after a yoga class. No trauma, no smoking, just a 6’4” guy who thought he was invincible. They stuck a needle in his chest in the ER and he cried like a baby. They told him to quit smoking even though he didn’t smoke. Then he flew to Florida three weeks later and had to be airlifted back. Don’t ignore the rules. This isn’t a scare tactic-it’s biology.

Wait so if you’re under 2cm and healthy you can just go home? I had a weird sharp pain last month and thought it was heartburn. I didn’t go to the doc. Should I get an xray? I’m 28, 5’11”, never smoked. But I did lift heavy weights last week…

So let me get this straight-smoking makes you 22x more likely to get your lung popped like a balloon and you still do it? Bro. You’re not a rebel. You’re a walking medical case study. Just quit. Your future self will thank you. Or not. Probably not. You’ll be back here asking why your third lung collapsed.

For anyone reading this-please don’t wait until you’re gasping. I had a tiny collapse after a coughing fit. I thought it was just allergies. Two days later I was in the ER with oxygen saturation at 87%. They said if I’d waited another 12 hours, I might’ve needed intubation. Don’t be like me. Get checked. Seriously.

It’s fascinating how the medical establishment still clings to chest X-rays like they’re relics of the 1980s. Ultrasound is faster, radiation-free, and more accurate in supine trauma patients-yet most ERs still make you wait 45 minutes for a radiologist to squint at a grainy image. This isn’t progress. It’s institutional inertia wrapped in white coats. The lung point is visible in seconds with a good probe. Why are we still doing this?

I’m from Kenya and we don’t have CT scanners in most rural clinics. We rely on clinical signs-reduced breath sounds, hyperresonance on percussion, sudden dyspnea. I’ve seen young men collapse after a sneeze and live because the nurses knew what to look for. Technology helps, but knowledge saves lives. Share this with your friends who think it’s just ‘a pulled muscle’.

Do not fly. Do not dive. Get follow-up imaging. Quit smoking. Undergo VATS after second episode. These are non-negotiables.